Lateral Dynamics of a Linear Single-Track Vehicle

Introduction

Early mathematical models describing the lateral dynamics of an automobile represented major advancements in vehicle dynamics. Among the automotive pioneers was the Cornell Aeronautical Laboratories (CAL), who sought a quantitative way of characterising directional control and stability. Using their expertise in studying aircraft dynamics, their research resulted in a set of equations that described lateral dynamics of a car.

In 1956, the findings at CAL were published in the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (IME). Two vehicle models were presented: a three-degree-of-freedom model presented by Leonard Segel, and a simplified two-degree-of-freedom model - also known as the bicycle model - presented by David Whitecomb and William Milliken.

Of the two models, the simpler two-degree-of-freedom model remains a cornerstone of vehicle dynamics. Its usefulness lies in its simplicity, both conceptually and computationally. The importance of this model is not to be understated; it is the first vehicle model presented in vehicle dynamics curriculum and serves as a foundational vehicle model in research literature.

As a tribute to this historic work, we present the equations-of-motion describing the lateral dynamics of a linear single-track vehicle.

Approach

The derivation is based on a force and moment balance with inertial reactions of a single-track vehicle. The formulae is derived symbolically using the Python package Sympy v1.1.1.

For a historic reference of this work, please refer to Chapter 5, Race Car Vehicle Dynamics by W.F. Milliken & D.L. Milliken.

For a derivation using work-energy methods, please refer to Chapter 1.3, Tyre & Vehicle Dynamics by H.B. Pacejka.

List of Symbols

Constants

- \(g\) represents the earth gravitation constant [\(m/s^2\)]

Variables

- \(t\) represents time [\(s\)]

- \(s\) represents complex frequency [-]

Vehicle States

- \(u\) represents the longitudinal velocity of the chassis centre-of-gravity [\(m/s\)]

- \(v\) represents the lateral velocity of the chassis centre-of-gravity [\(m/s\)]

- \(r\) represents the yaw velocity of the chassis centre-of-gravity [\(rad/s\)]

- \(\beta\) represents chassis slip angle at the centre-of-gravity [\(rad\)]

- \(\delta\) represents steered wheel angle of the front axle [\(rad\)]

Vehicle Properties

- \(m\) represents the vehicle mass [\(kg\)]

- \(I\) represents the vehicle yaw inertia [\(kg \cdot m^2\)]

- \(l_a\) represents the length from the chassis centre-of-gravity to the front axle [\(m\)]

- \(l_b\) represents the length from the chassis centre-of-gravity to the rear axle [\(m\)]

- \(W_f\) represents the vertical load on the front axle [\(N\)]

- \(W_r\) represents the vertical load on the rear axle [\(N\)]

Tire States

- \(\alpha_f\) represents the front axle effective slip angle [\(rad\)]

- \(\alpha_r\) represents the rear axle effective slip angle [\(rad\)]

Tire Properties

- \(C_f\) represents the front axle effective cornering stiffness [\(N/rad\)]

- \(C_r\) represents the axle axle effective cornering stiffness [\(N/rad\)]

Cornering Compliances

- \(D_f\) represents the front axle cornering compliance [\(\frac{rad}{g}\)]

- \(D_r\) represents the rear axle cornering compliance [\(\frac{rad}{g}\)]

Forces

- \(F_{y,f}\) represents the lateral force developed at the front axle [\(N\)]

- \(F_{y,r}\) represents the lateral force developed at the rear axle [\(N\)]

Base Assumptions

Force and Moment Balance

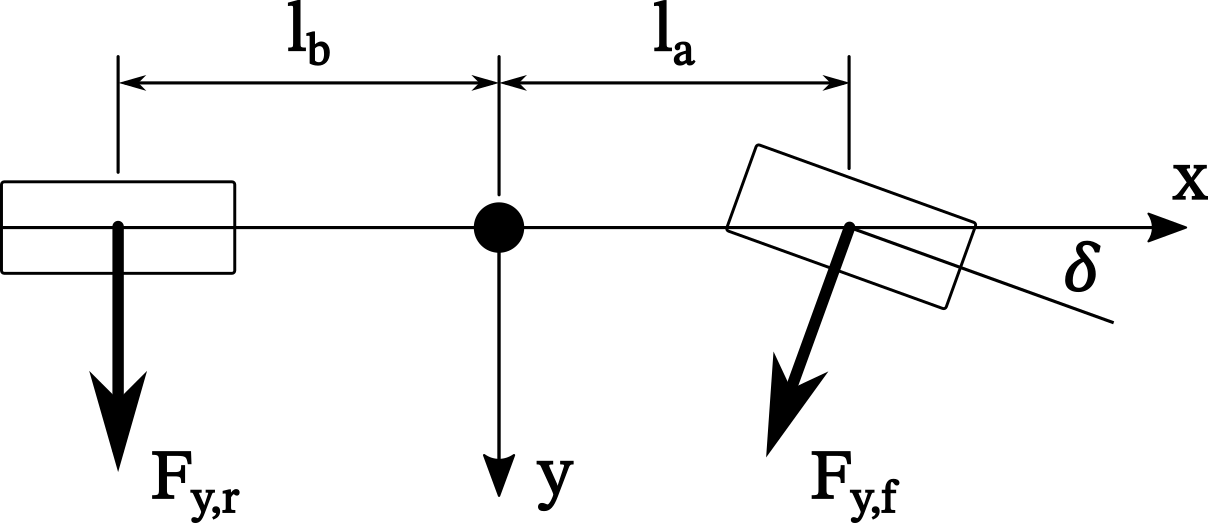

The force and moment balance of a single-track bicycle is described by the following free-body diagram:

Based on the free-body diagram, the equations describing the force and moment balance are governed by the following equations:

\[m(\dot{v} + u \cdot r) = F_{y,f} \cos{\left(\delta\right)} + F_{y,r}\] \[I \dot{r} = a F_{y,f} \cos{\left(\delta\right)} - b F_{y,r}\]To simplify the derivation, we assume small angle variations in the steered angle, \(\delta\). By this assumption, we linearize the \(\cos{\left(\delta\right)}\) about an operating region around \(\delta = 0\) such that \(\cos{\left(\delta\right)} \simeq 1\). Therefore, the force and moment balance equations become:

\[m(\dot{v} + u \cdot r) = F_{y,f} + F_{y,r}\] \[I \dot{r} = a F_{y,f} - b F_{y,r}\]Tire Model

The lateral force generated by the tires is assumed to be a linear function of the slip angle.

\[F_{y,f} = -C_f \alpha_f\] \[F_{y,r} = -C_r \alpha_r\]The linear stiffness assumption is only valid for small slip angles. Generally speaking, the validity of this assumption restricts analysis to maneuvers low lateral accelerations.

Note: the cornering stiffness \(C_f\) and \(C_r\) represents the effective cornering stiffness of the axle.

Slip Angles

The axle slip angle is defined as the angle between the direction of heading and the direction of the tire centreline. This angle is modelled as the arctangent of velocity components of each axle.

\[\alpha_f = \arctan\left(\frac{v + r \cdot a}{u}\right) - \delta\] \[\alpha_r = \arctan\left(\frac{v - r \cdot b}{u}\right)\]To simplify the derivation, we assume small angle variations in the axle slip angles, \(\alpha\). By this assumption, we linearize the function \(f(x) = \arctan{\left(x\right)}\) about an operating region around \(x = 0\) such that \(\arctan{\left(x\right)} \simeq x\). Therefore, the slip angle equations become:

\[\alpha_f = \frac{v + r \cdot a}{u} - \delta\] \[\alpha_r = \frac{v - r \cdot b}{u}\]Note: the singularity at \(u = 0\) causes this model to only be valid for non-zero longitudinal velocities.

Base Derivation

Given the base assumptions, we can develop a set of linear differential equations with lateral velocity and yaw velocity as state variables.

Differential, state-space and transfer function representations of the model are provided.

Differential Form

\[\dot{v} = \frac{(-C_f - C_r) v + (-C_f l_a + C_r l_b - mu^2) r}{mu} + \frac{C_f \delta}{m}\] \[\dot{r} = \frac{(-C_f l_a + C_r l_b) v - (C_f l_a^2 + C_r l_b^2) r}{Iu} + \frac{C_f l_a \delta}{I}\]State-Space Form

\[\begin{bmatrix} \dot{v} \\ \dot{r} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{-C_f - C_r}{mu} & \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{mu} - u \\ \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{Iu} & \frac{-C_f l_a^2 - C_r l_b^2}{Iu} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} v \\ r \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \frac{C_f}{m} \\ \frac{C_f l_a}{I} \end{bmatrix} \delta\]Transfer Function Form

\[\frac{V(s)}{\delta(s)} = \frac{\frac{C_f}{m} s + \frac{C_f}{Imu} (C_r l_a l_b + C_r l_b^2 - l_a mu^2)}{s^2 + \left(\frac{C_f + C_r}{mu} + \frac{C_f l_a^2 + C_r l_b^2}{Iu}\right) s + \frac{C_f C_r (l_a + l_b)^2}{Imu^2} + \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{I}}\] \[\frac{R(s)}{\delta(s)} = \frac{\frac{C_f l_a}{I} s + \frac{C_f C_r (l_a + l_b)}{Imu}}{s^2 + \left(\frac{C_f + C_r}{mu} + \frac{C_f l_a^2 + C_r l_b^2}{Iu}\right) s + \frac{C_f C_r (l_a + l_b)^2}{Imu^2} + \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{I}}\]Derivation using Chassis Slip Angle as a State Variable

Depending on application, it may be useful to describe the vehicle using the chassis slip angle.

The chassis slip angle is defined as the angle between the direction of heading at the vehicle centre-of-gravity and the direction of the vehicle centreline. This angle is modelled as the arctangent of velocity components at the vehicle centre-of-gravity.

\[\beta = \arctan{\left(\frac{v}{u}\right)}\]To simplify the derivation, we assume small angle variations in the chassis slip angle, \(\beta\). By this assumption, we linearize the function \(f(x) = \arctan{\left(x\right)}\) about an operating region around \(x = 0\) such that \(\arctan{(x)} \simeq x\). Therefore, the chassis slip angle equations becomes:

\[\beta = \frac{v}{u}\]We make the following substitutions to change the state variable from \(v\) to \(\beta\):

\[v = u \cdot \beta\] \[\dot{v} = u \cdot \dot{\beta}\]Differential Form

\[\dot{\beta} = \frac{u (-C_f - C_r) \beta + (-C_f l_a + C_r l_b - mu^2) r}{mu^2} + \frac{C_f \delta}{mu}\] \[\dot{r} = \frac{u (-C_f l_a + C_r l_b) \beta - (C_f l_a^2 + C_r l_b^2) r}{Iu} + \frac{u C_f l_a \delta}{I}\]State-Space Form

\[\begin{bmatrix} \dot{\beta} \\ \dot{r} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{-C_f - C_r}{mu} & \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{mu^2} - 1 \\ \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{I} & \frac{-C_f l_a^2 - C_r l_b^2}{Iu} \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \beta \\ r \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \frac{C_f}{mu} \\ \frac{C_f l_a}{I} \end{bmatrix} \delta\]Transfer Function Form

\[\frac{\beta(s)}{\delta(s)} = \frac{\frac{C_f}{mu} s + \frac{C_f}{Imu^2} (C_r l_a l_b + C_r l_b^2 - l_a mu^2)}{s^2 + \left(\frac{C_f + C_r}{mu} + \frac{C_f l_a^2 + C_r l_b^2}{Iu}\right) s + \frac{C_f C_r (l_a + l_b)^2}{Imu^2} + \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{I}}\] \[\frac{R(s)}{\delta(s)} = \frac{\frac{C_f l_a}{I} s + \frac{C_f C_r (l_a + l_b)}{Imu}}{s^2 + \left(\frac{C_f + C_r}{mu} + \frac{C_f l_a^2 + C_r l_b^2}{Iu}\right) s + \frac{C_f C_r (l_a + l_b)^2}{Imu^2} + \frac{-C_f l_a + C_r l_b}{I}}\]Derivation using Cornering Compliances

Depending on application, it may be useful to describe the vehicle using the axle cornering compliance instead of effective axle cornering stiffness.

The definition of cornering compliance is given as:

\[D_f = \frac{W_f}{C_f}\] \[D_r = \frac{W_r}{C_r}\]The vertical load on each axle, \(W_f\) and \(W_r\), can be expressed in terms of the vehicle mass and geometry.

\[W_f = \frac{mgl_b}{l_a + l_b}\] \[W_r = \frac{mgl_a}{l_a + l_b}\]Given this relationship, the cornering compliance can be expressed by the following equations:

\[D_f = \frac{mgl_b}{\left(l_a + l_b\right)C_f}\] \[D_r = \frac{mgl_a}{\left(l_a + l_b\right)C_r}\]We make the following substitutions to change the variables from \(C_f\), \(C_r\) to \(D_f\), \(D_r\):

\[C_f = \frac{mgl_b}{\left(l_a + l_b\right)D_f}\] \[C_r = \frac{mgl_a}{\left(l_a + l_b\right)D_r}\]Differential Form

\[\dot{\beta} = \frac{g u (-D_f l_a - D_r l_b) \beta + \left(-D_f D_r u^2 (l_a + l_b) + (D_f - D_r) g l_a l_b \right) r}{D_f D_r u^2 (l_a + l_b)} + \frac{g l_b \delta}{D_f u (l_a + l_b)}\] \[\dot{r} = \frac{m g u (D_f - D_r) (l_a l_b) \beta - (D_f l_b - D_r l_a) (g l_a l_b m) r}{D_f D_r I u (l_a + l_b)} + \frac{g l_a l_b m \delta}{D_f I (l_a + l_b)}\]State-Space Form

\[\begin{bmatrix} \dot{\beta} \\ \dot{r} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} - \frac{g \left(D_f l_{a} + D_r l_{b}\right)}{D_f D_r u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} & \frac{- (D_f D_r u^2)(l_a + l_b) + (D_f - D_r) g l_a l_b}{D_f D_r u^2 \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} \\ \frac{g l_{a} l_{b} m \left(D_f - D_r\right)}{D_f D_r I \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} & - \frac{g l_{a} l_{b} m \left(D_f l_{b} + D_r l_{a}\right)}{D_f D_r I u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)}\\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \beta \\ r \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} \frac{g l_{b}}{D_f u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} \\ \frac{g l_{a} l_{b} m}{D_f I \left(l_{a} + l_b\right)} \end{bmatrix} \delta\]Transfer Function Form

\[\frac{\beta(s)}{\delta(s)} = \frac{\frac{g l_{b}}{D_f u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} s + \frac{g l_{a} l_{b} m \left(- D_r u^{2} + g l_{b}\right)}{D_f D_r I u^{2} \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)}}{s^2 + \frac{\left(( D_f l_a + D_r l_b ) I + ( D_f l_b + D_r l_a ) m l_a l_b \right) g}{D_f D_r I u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} s + \frac{\left((D_f - D_r) u^{2} + (l_{a} + l_{b}) g\right) g l_{a} l_{b} m }{D_f D_r I u^{2} \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} }\] \[\frac{R(s)}{\delta(s)} = \frac{\frac{g l_{a} l_{b} m}{D_{f} I \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} s + \frac{g^{2} l_{a} l_{b} m}{D_{f} D_{r} I u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)}}{s^2 + \frac{\left(( D_f l_a + D_r l_b ) I + ( D_f l_b + D_r l_a ) m l_a l_b \right) g}{D_f D_r I u \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)} s + \frac{\left((D_f - D_r) u^{2} + (l_{a} + l_{b}) g\right) g l_{a} l_{b} m }{D_f D_r I u^{2} \left(l_{a} + l_{b}\right)}}\]Conclusion

The amateur driver of today has more data available than ever before. Modern data acquisition systems make it easier than ever to observe the vehicle state, especially with the increased capabilities of modern safety systems. However, making sense of this data remains a challenge, especially in the context of vehicle handling.

The equations-of-motion provides the basis to study vehicle handling. The advantage of this approach is the ability to quantify handling attributes and qualify subjective observations made on the race track.

In the next few articles, we explore the classical techniques in analyzing vehicle handling. We look back on the historic developments in vehicle dynamics and see how there is still much to learn from the founders of the science.

Interested in the derivation code? Browse the code here!

References

- Milliken, William F., and Douglas L. Milliken. Race car vehicle dynamics. Vol. 400. Warrendale: Society of Automotive Engineers, 1995.

- Pacejka, Hans. Tire and vehicle dynamics. Elsevier, 2005.

- Yih, Paul, Jihan Ryu, and J. Christian Gerdes. “Modification of vehicle handling characteristics via steer-by-wire.” American Control Conference, 2003. Proceedings of the 2003. Vol. 3. IEEE, 2003.